The Science of Stress and the Strength to Cope

October 2025

What does it mean to feel stressed? While the language we use today may be modern, the experience of stress is as ancient as humanity itself. Across time and tradition, philosophers and healers have sought to understand how our thoughts, emotions, and bodies respond to challenges and change. As the Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius once said, “If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself but to your own estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.”

This timeless insight reminds us that stress isn’t just about what happens to us— it’s deeply tied to how we perceive and respond to those events. Whether it’s an unexpected change, a looming threat, or a painful loss, the way we interpret these moments shapes the emotional and physical toll they take on us.

Today, stress can be understood as an unpleasant emotional state that triggers cognitive, behavioral, physiological, and biochemical responses aimed at helping us deal with a perceived challenge or threat. A traffic jam, a looming deadline, or a missed appointment can produce measurable stress responses, just like the devastating loss of a loved one or a sudden illness. Both minor and major stressors affect our health over time.

These stressors—defined as environmental changes that require an individual to adapt—become particularly taxing when they demand multiple adjustments simultaneously. The more demands placed on an individual, the more severe the stress response becomes.

.png)

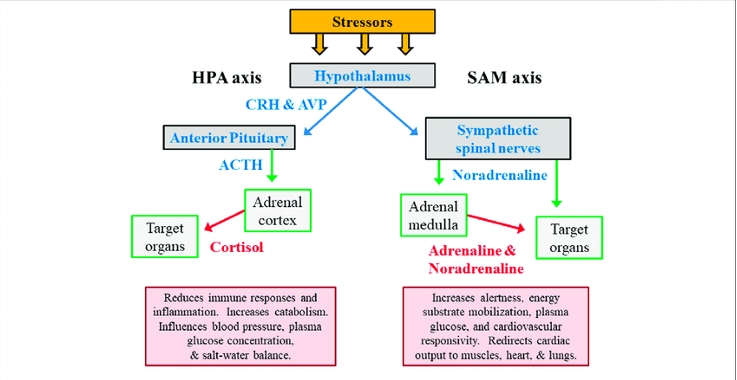

The Biology of Stress: Fight-or-Flight in the Body

To understand stress, we have to understand the physiological systems that mobilize us in moments of challenge or threat.

When the brain perceives stress, two central systems activate:

The SAM Axis (Sympathetic-Adrenal-Medullary):

This is our classic "fight-or-flight" system. The hypothalamus triggers the release of epinephrine (adrenaline) and noradrenaline, first as neurotransmitters, and then, via the adrenal medulla, as hormones in the bloodstream. These chemicals increase heart rate, respiration, and muscle strength, preparing the body for rapid action.

The HPA Axis (Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal):

If the situation is perceived as a threat, not just a challenge, the amygdala signals the hypothalamus to release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). This activates the pituitary gland, which then releases adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH tells the adrenal glands to release cortisol, which fuels the stress response by boosting energy, but can suppress the immune system if overactivated. These systems are adaptive in the short term. But over time, chronic activation of the HPA axis can lead to immune dysregulation, burnout, anxiety, and disease.

.png)

Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome: Stress in Phases

One of the first scientists to explore this systematically was Hans Selye, who developed the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS)—a model showing how organisms respond to prolonged stress in three stages:

- Alarm Phase: The body mobilizes its defenses through the activation of the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axes.

- Resistance Phase: The body adapts and copes with the stress.

- Exhaustion Phase: If stress continues too long, the body depletes its resources.

In one study, Selye exposed rats to physical stressors, such as forced swimming. The rats showed physical decline over time. But intriguingly, when rats were exposed to the same stressor a second time after having survived it once, they no longer exhibited the same stress symptoms—they had learned that survival was possible. The rats’ bodies responded less intensely the second time because they had learned they could survive. This suggests that when we perceive a challenge as manageable, our stress response can become more subdued.

Selye helped us understand what stress does to the body, but what about what’s happening in the mind? That’s where the cognitive model of stress comes in, focusing on how we interpret and evaluate the challenges we face.

.png)

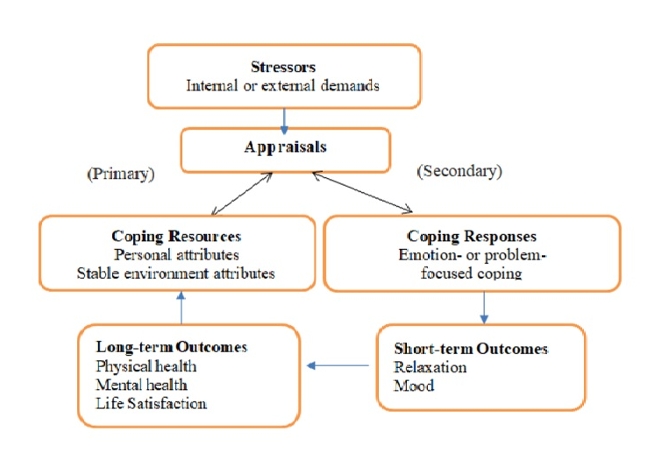

The Cognitive Model of Stress: What We Think Matters

One of the most influential ways to understand stress comes from psychologist Richard Lazarus, who proposed that stress is not just about the demands we face, but how we interpret and respond to those demands.

This process, known as the cognitive appraisal model, can be broken down into several steps:

1. Stressors

These are internal or external demands, anything from a tight deadline to a major life change, that place pressure on us.

2. Appraisals

When a stressor is present, we go through two types of appraisals:

- Primary Appraisal: Is this situation harmful, threatening, or challenging to me?

- Secondary Appraisal: Do I have the personal or environmental resources to cope with this?

Together, these appraisals determine how we experience and respond to stress.

3. Coping Resources & Responses

If we feel we can cope, we are more likely to tap into our personal strengths or stable support systems and respond with problem-solving or emotion-focused coping strategies.

If we feel we can’t cope, our stress response intensifies—activating both the SAM and HPA systems, and increasing the risk of emotional and physical strain.

4. Outcomes

How we cope leads to different short- and long-term results:

- Short-Term: Improved relaxation and mood

- Long-Term: Better physical and mental health, increased life satisfaction

The more confident we are in our ability to cope, the more likely we are to experience healthier outcomes.

.png)

The Akhila Connection: Stress Management as Empowerment

So, how does this relate to Akhila Health?

At Akhila Health, our mission is to expand access to holistic wellness tools that help underserved women develop healthy stress-coping behaviors. We offer workshops that raise awareness of stressors and help participants recognize their own physical, emotional, and mental states, while introducing practical tools for self-regulation. In addition, through our partnerships, we offer practices such as yoga, breathwork, meditation, art, and guided movement like qigong. Some of these practices are woven into our presentations, while others are offered as separate, stand-alone activities. Together, these offerings support a shift from chronic activation to internal regulation.

These practices aren’t just “feel-good” interventions. They promote challenge appraisals, reinforce a sense of safety, and reduce the biological wear and tear caused by unprocessed stress.

From Selye’s research on stress to real-life experiences, one thing is clear - when we recognize that a challenge is manageable, our stress response changes, and we become more capable of adapting. At Akhila, we aim to offer more than a moment of calm—we offer tools and support that empower women to face challenges with resilience and self-trust.

Stress is part of being human, but chronic, unprocessed stress doesn’t have tobe.

When we understand how stress works, from our biology to our beliefs, we can take steps to respond with compassion rather than fear. At Akhila Health, we believe that healing starts with understanding and grows through consistent support and practice.

We provide a wide range of stress-management tools and strategies. Each workshop begins with centering the body and mind through gentle movement, breathwork, and visualization. From there, we transition to interactive lessons, focusing on experiential education that deepens our understanding of the mindemotion connection and offers practical techniques for achieving everyday balance. Throughout the session, open-ended questions and group discussions invite every woman to look inward, explore her own experiences, and define a personal path toward her best self.

Because healing doesn’t just happen in moments of calm. It happens in the tools we build, the spaces we share, and the courage we cultivate together.

.png)

References

Armstrong, Lawrence & Bergeron, Michael & Lee, Elaine & Mershon, James & Armstrong, Elizabeth. (2022). Overtraining Syndrome as a Complex Systems Phenomenon. Frontiers in Network Physiology. 1. 794392. 10.3389/fnetp.2021.794392.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 50(5), 992.

Higuera, V. (2018, October 6). General adaptation syndrome: Your body’s response to stress. Healthline. Retrieved [2025, April 26], from https://www.healthline.com/health/general-adaptation-syndrome

.png)

Join the Cause

Wondering how you can help?

Want to help underserved women access critical stress management services?

Together we can build a happier and healthier future for all women